A confession: I am haunted. Yes, I’m lousy with ghosts. No big deal, all libraries are haunted. Ever notice how the more haunted the house, the bigger the library? Ever see Ghostbusters?

There’s something about winter, too, particularly a stormy winter such as this one, that draws the ghosts out of the walls, particularly if those walls are lined with books. Come a snowfall, I’m sure to find LW poking around my history and biography sections where ghosts like to congregate.

As the Arctic Vortex descended upon the City last month, LW picked up a book about the relationship between the Booth brothers, Edwin and John Wilkes, that she’d bought two years ago. When she was deep into this book, an email from Edwin Booth popped up in her In Box. At least that’s my theory–I told you the ghosts come out this time of year. She claimed it was just a generic invitation from the office of The Obscura Society to which she subscribes. No matter, for the email invited her to tour The Players, the historic social club Edwin founded on Gramercy Park South in 1888. Regardless of who actually sent it, I think Edwin wanted her to come.

One way or another, LW got to tour The Players, which she had longed to do for many years. Whenever she was in the neighborhood, she would seek out the building to linger a moment near a window, not unlike the woman in this photo (taken before the current scaffolding was erected on the building’s front), hoping to catch a glimpse of its interior.

Edwin Booth was the most celebrated American actor of his day. His fame was to be eclipsed, however, by the infamy of his younger brother John Wilkes Booth, the assassin of President Lincoln. It is Edwin, however, who interests LW, and what interests her tends to interest me. I couldn’t wait to hear about the tour.

She toured, she saw, and she returned with a few photographs and perhaps a dusting of ghost. She told anyone who would listen how she had felt Edwin’s presence throughout the 19th century mansion. I had to settle for poring over the rather poor quality photographs she took, some of which I will show here. (Her camera phone was old, she complained, and the rooms were dark.)

I am intrigued by this photograph. I ask: Do you see a ghost here? Is it me, or is there something spectral here? Is that a large hand I spy with my little bookish eye, reaching down from the ceiling?

The photo shows a glass tabletop reflecting a window (semi-covered by temporary scaffolding) that overlooks Gramercy Park. [At the Park’s center is the statue of Edwin Booth shown in the photograph at the top of this post, taken in a warmer season.] I confess to having rotated the photo upside down; I thought it might be easier to view this way. The glass protects two papers and a photograph of Edwin. The papers are copies of the same letter; one typed, one handwritten.

The letter is addressed to the People of the United States. It expresses Edwin’s and his family’s abhorrence at his brother’s crime and announces his (Edwin’s) retirement from acting. John Wilkes was still at large at the time Edwin published this letter and would be dead within six days of its writing. Edwin had been a staunch supporter of the Union cause and President Lincoln. In an uncanny coincidence, Edwin had once even saved the President’s son Robert from possible injury or death at a train station, pulling him up by his collar to the platform from where the young man had fallen just as the train began to move. Edwin would continue to be greatly admired by his audience despite his brother’s treacherous act, and they did not hold him to his retirement vow. These letters are just a few of the extraordinary items on display at The Players, where Edwin lived out the last years of his life.

LW was not able to see every room of The Players, but she did see the Grill Room, the social heart of the Club. Here is the bar at the room’s front end. Booth himself requested that passages from Shakespeare be inscribed on the walls wherever they seemed fitting, and several of those can be seen here.

Next stop was the library, which was particularly dark, probably so as not to wake the ghosts.

Edwin Booth’s personal collection of theatrical books, scripts, playbills, photographs, costumes, props, and memorabilia became the base of the library’s holdings. LW snapped this photo on her way out, and those books certainly do have the haunts about them.

Booth’s costumes and props are displayed along halls throughout the building. I wonder which role he was playing when he wore this robe—Cardinal Richelieu, perhaps? (I think I’m scared now.)

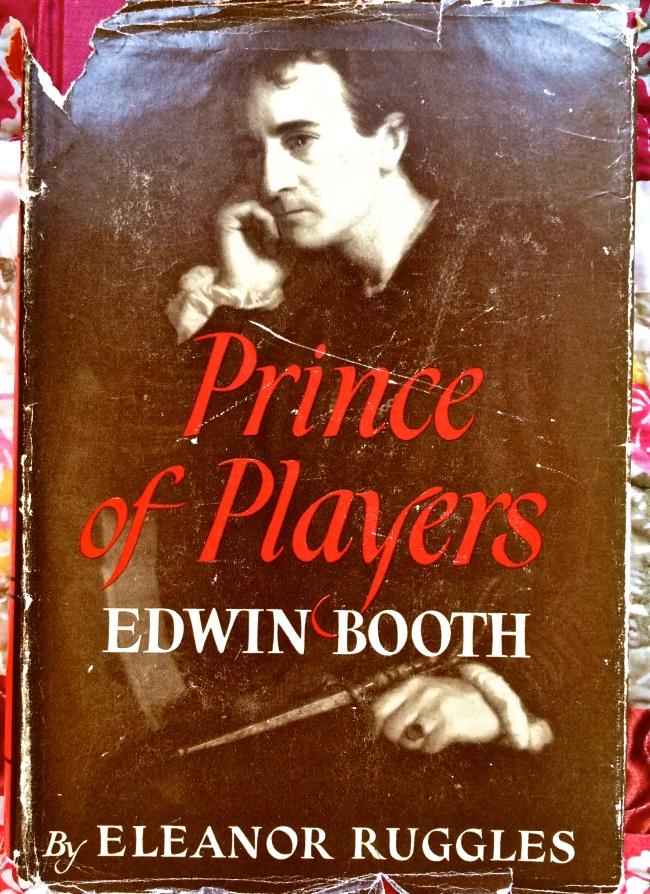

But what she wanted most to see was the inner sanctum of Edwin’s third floor apartment, seldom opened to the public, and which had been left more or less in place as it was when he died there. She first read about this room years ago in a popular biography of Booth called The Prince of Players by Eleanor Ruggles. Her beat-up copy is a Book-of-the-Month edition she picked up on the cheap at The Strand, but at least it has its jacket, which shows Booth in the prime of his life–and looks.

A passage of this book impressed her so deeply that she remembered it as being the opening scene, though it does not actually appear until page 346. It describes Edwin in his last years by the window of his room at The Players “…a still figure reclining on a sofa, so nearly perfectly quiet he could hardly be distinguished in the darkening room—while the church clocks chimed from near and far, their strokes emphasizing the desertedness of the city so late in these summer nights.”

The passage continues: “Sometimes he dozed. Sometimes his mind seethed—‘vulture thoughts,’ he called them—and he stared out with desperate wakefulness at Gramercy Park, whose trees were bathed in the light of a moon more remote and silvery than the low-hanging California moon. One o’clock struck, and after a long interval, two, then three. Often he heard four strike, and he looked expectantly for the gradual paling of the sky in the east; watched the slow taking shape of objects in his room; heard the clatter of milk carts, the imperative whistles bidding others to work. He called these his ‘vulture hours.’”

The tour culminated in this very apartment, where LW took the photo of the “sofa” described above, as well as his bed, seen below.

My recent posts have described LW’s fascination with windows and scenes or objects displayed behind or under glass. A related interest of hers, as my heavy shelves will attest, is rooms and interiors, particularly as described in books, fiction or non-fiction. She has even kept a notebook of interesting descriptions of rooms. This one, from pages 365-6 of the Ruggles book, is a favorite:

“Booth’s room was divided by a fretwork arch and draw curtain that shut off the alcove where his bed was. The brass bed, which had a tester and curtains, was spread with the crazy quilt Mrs. Anderson [wife of an old actor friend] had made him. On the bureau in the alcove were two small photographs, one of his mother, stern and sad in old age, and one of his grandchildren. To the left of the bed in the most retired position in the room was the picture of John Wilkes from which Edwin had never parted…

“On the center table under the chandelier in the main section of the room lay a bronze cast of Booth’s hand holding [his daughter] Edwina’s baby hand. To the right of the fireplace leered three skulls, all used in Hamlet…”

You can see the crazy quilt on the bed in the photo above. The picture of his brother hard to see here, but it, too, is still in place, the uppermost of the two pictures hanging to the left of the bed (the viewer’s right) in the white matted frame. And you might be able to make out the bronze cast of hands on the table in the photograph below.

The description continues: “His desk stood against the wall, neatly piled with sheets of the club writing paper embossed with masks of Comedy and Tragedy. Above the desk was a portrait of his father and just below the portrait he had fixed appropriately a panel hewn out of the wood of the giant cherry tree from the farm in Maryland. On the wall nearest the window hung the most remarkable picture in the room, of Mary Devlin.”

That portrait is directly in the line of vision from the daybed. Many tragedies stalked Edwin, not the least of which was the death of his beautiful young wife Mary. Adding to his pain was the guilt he felt from knowing he had been distracted by drink when notices of Mary’s sudden illness arrived—she was in Boston and he in New York at the time—and he had arrived too late to be with her at her end.

LW has a small but interesting collection of books about Edwin Booth, and I will discuss some of them in the Part II of my post. I’m not sure if Edwin is haunting us, or if we are haunting him.

As I entered each room with you and LW as my guide I could smell the old air welcoming me. My eyes scanned the room for light and shadow of any spirits that were there watching the tour pass through the room. Long ago my Mom taught me the importance of journaling and how it creates pictures better than photos. But photos of photos and through glass bring on spirit of their own. I too grew up in a haunted house which also had a library in the room that was once mine. The house was filled with books, filled with photos, memories and later the smell of the old room. Thank you for taking me “home” again.

Oh, how I’d love to hear more about your library in your haunted house! And your mom must have been an incredible person; she still has such presence!

Excellent! Can’t wait for part 2. “Prince of Players” was made into a film starring Richard Burton as Edwin Booth. It’s one of his best film performances in my opinion. I think he might have been somewhat ‘inspired’.

BTW. Believe it or not, I had never read “Prince of Players”. Found it and read it in two sittings. what a rich description of the times. I have an even greater respect for “Ned” because of it. Thanks for the ‘bug’ in my ear.

You are welcome. Have you had a chance to read “My Thoughts Be Bloody” by Nora Titone? Its so…Shakespearean!

Thanks for the suggestion. Just found out about it the other day. My very next endeavour.

Cheers.

Looks like I have to get to Edwin Booth – Part II!