Tags

After Visiting Friends, Books about Fathers, Chicago, Fathers, Ghosts, Memories of Fathers, Michael Hainey

Hauntings. Resonances. Melancholy. Delicious melancholy. Chicago.

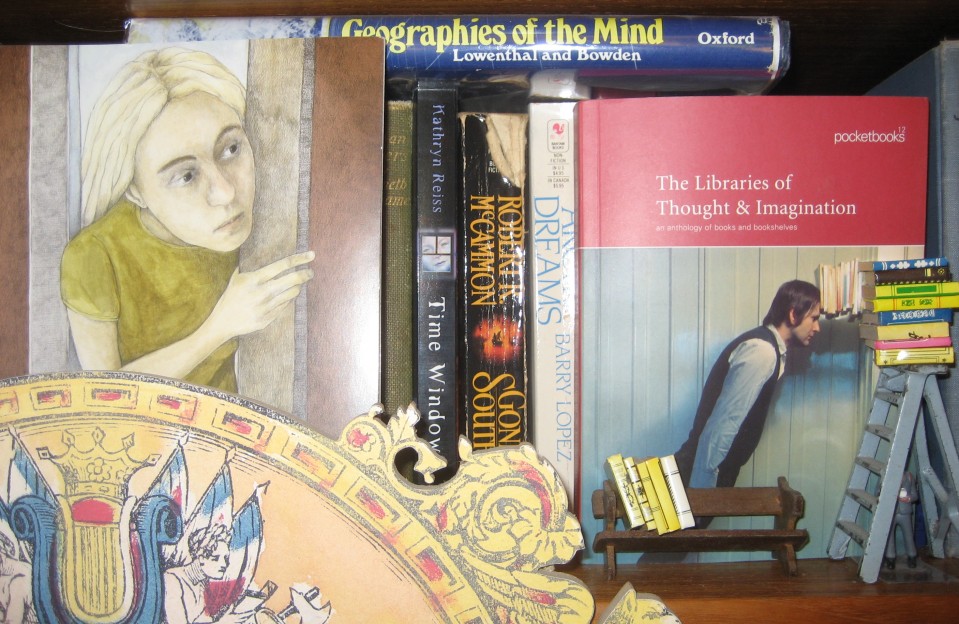

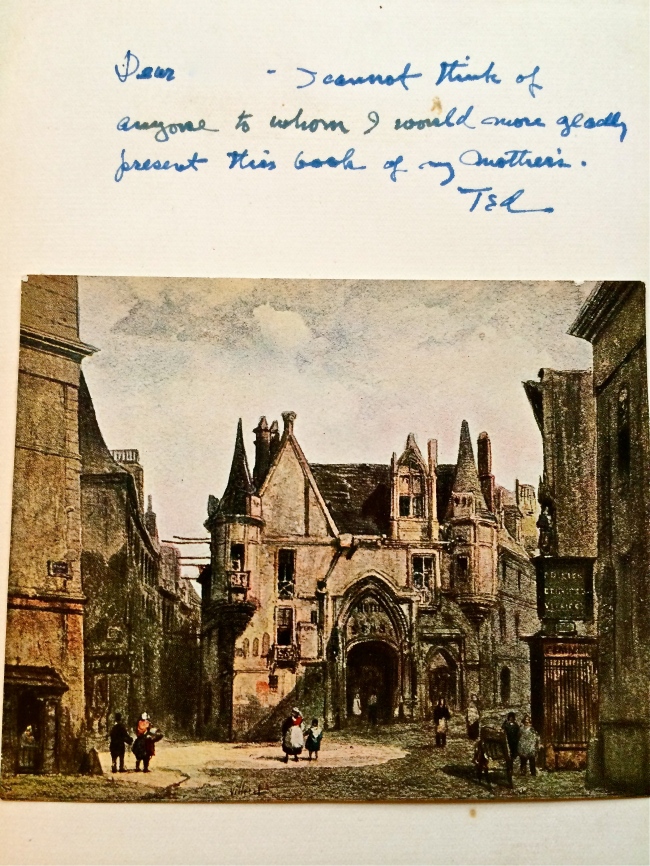

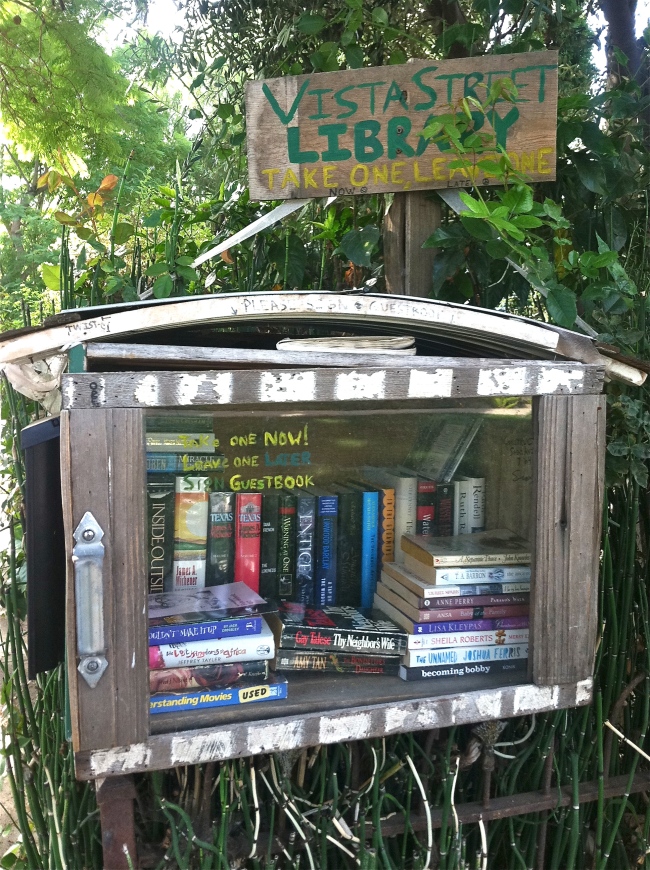

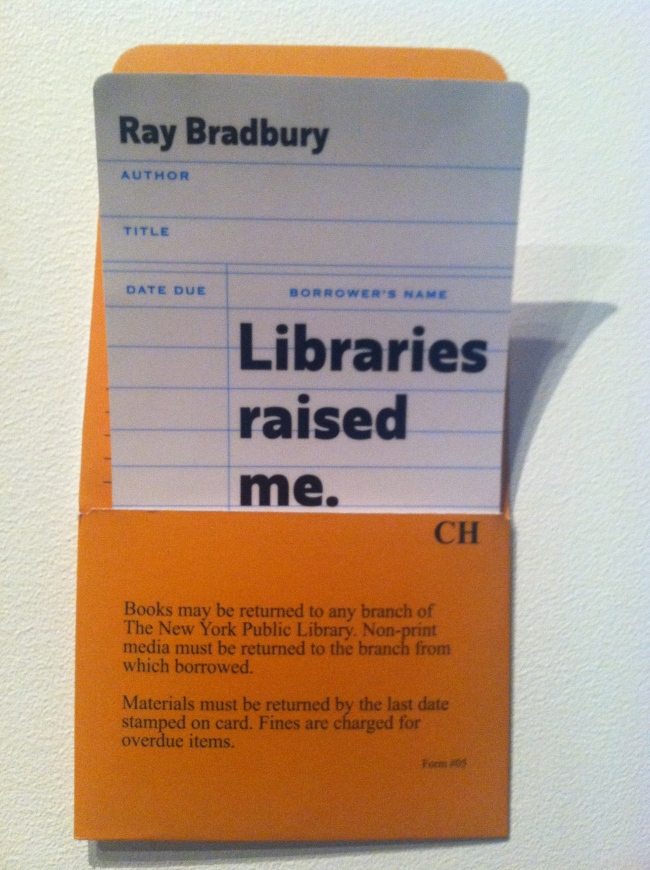

In April LW returned to Chicago, one of her favorite cities, for the first time in five years. She went with no agenda aside from visiting a few friends. She did, however, go with her usual travel strategy of giving herself over to the serendipity of books.

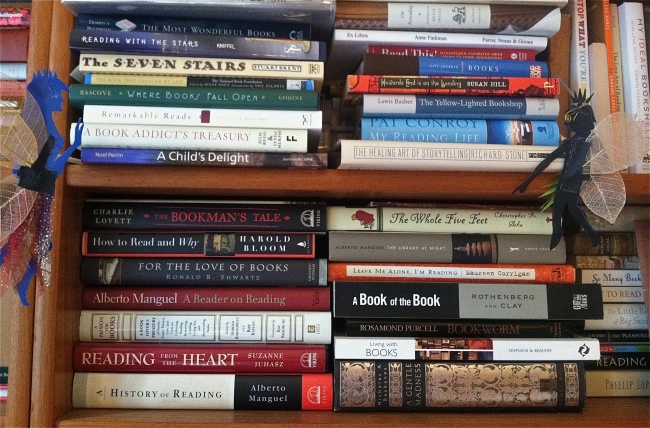

Which is why her first destination was the Unabridged Bookstore on Broadway in the Lakeview neighborhood, a few blocks from where her son once lived. This store is one of her favorites, a browser’s delight because of the thoughtful, passionate reviews taped to the bookshelves by the young staff.

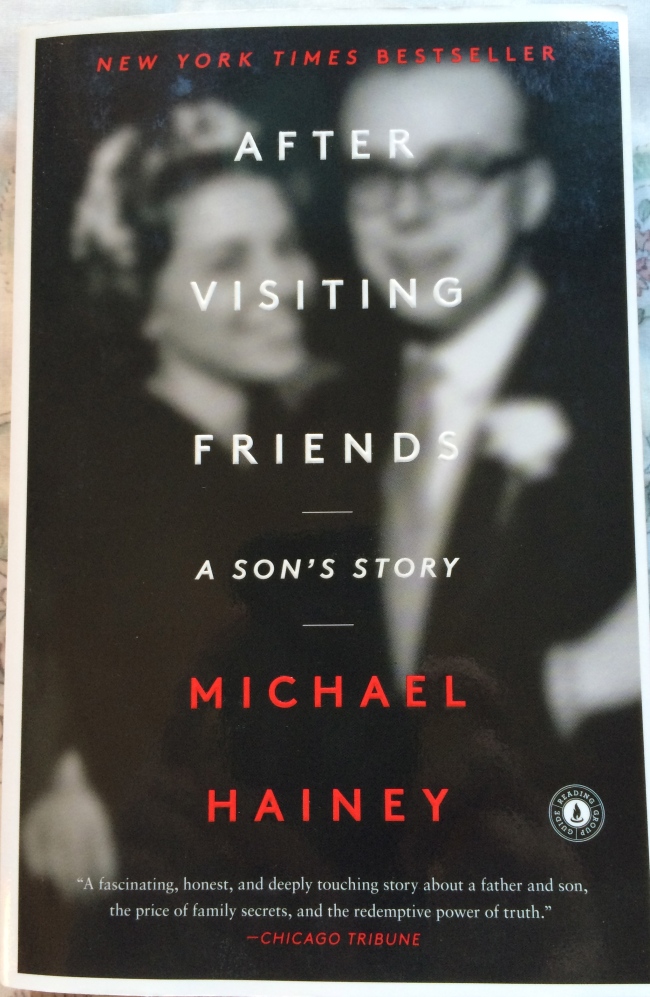

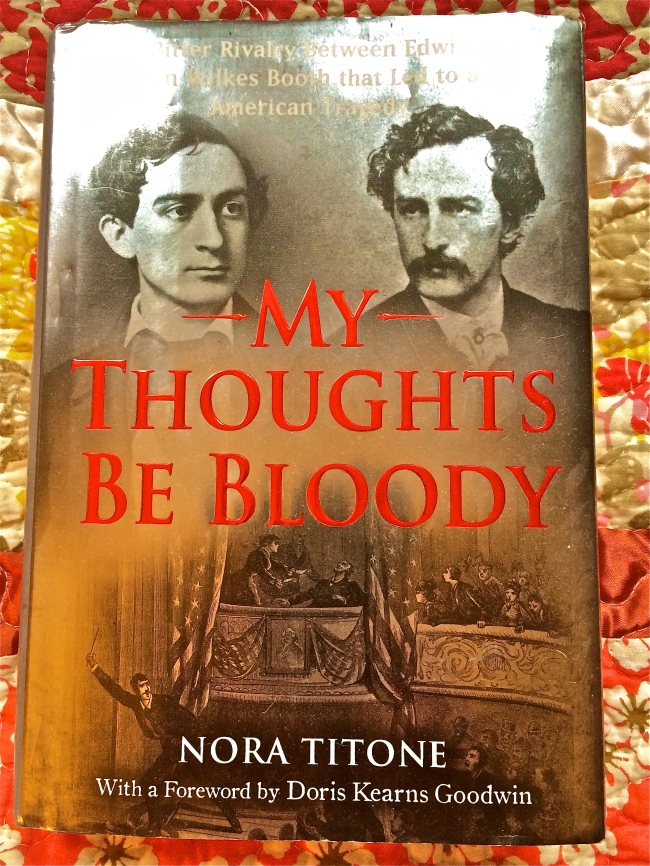

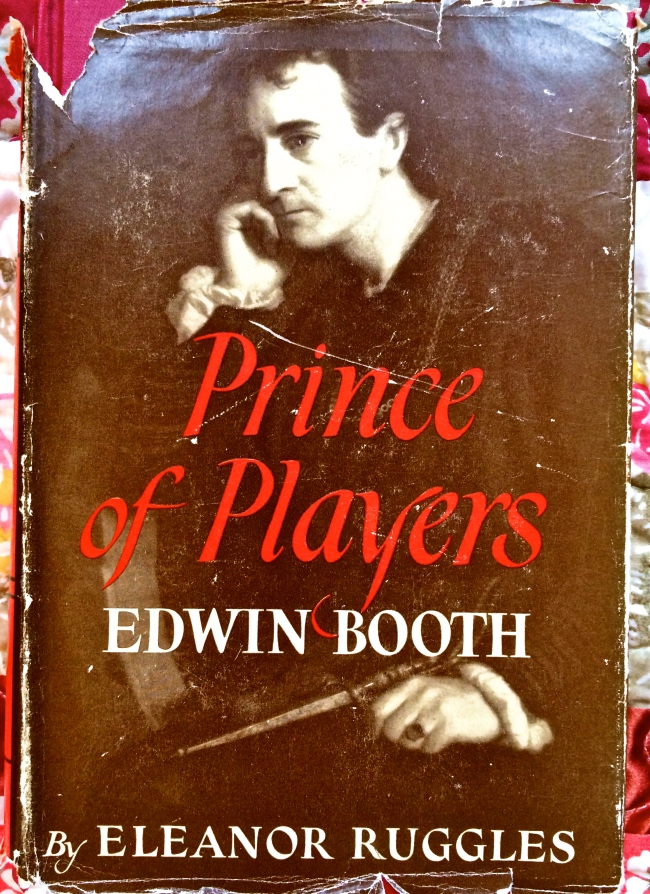

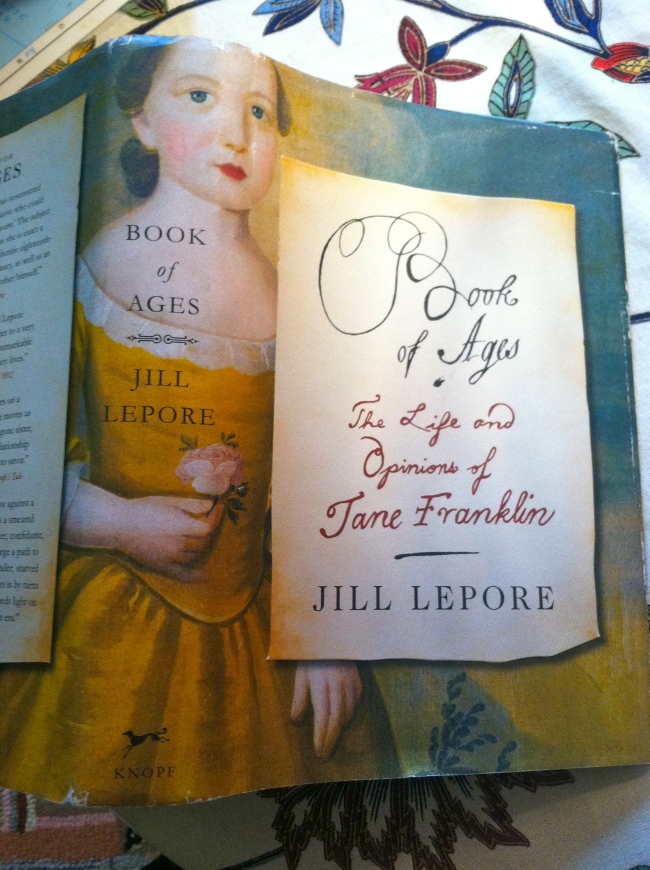

That day one of those reviews, hand-written on an index card, drew her to a book called After Visiting Friends – A Son’s Story by Michael Hainey.

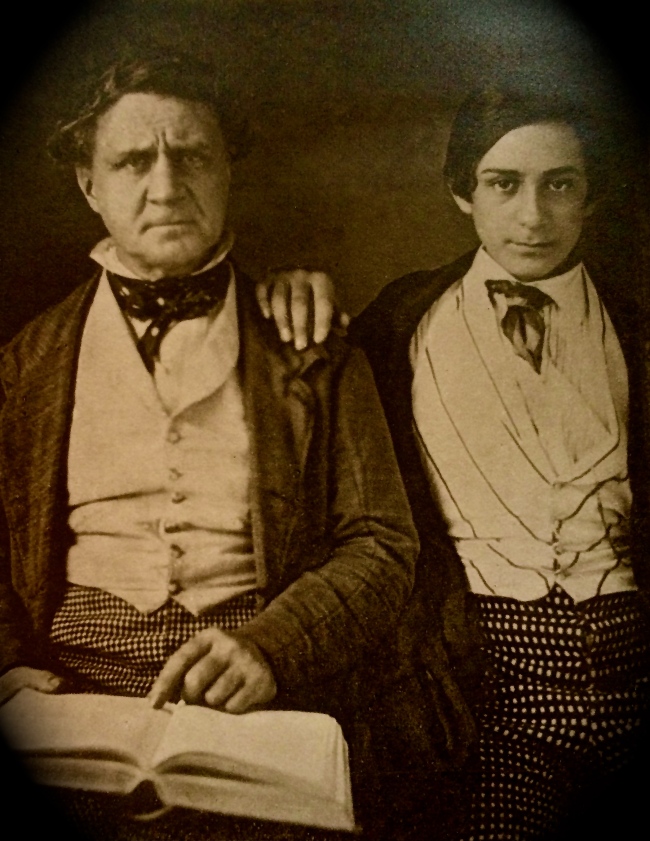

From the card and the cover she learned that Hainey’s father, a Chicago newspaperman, had died under mysterious circumstances when his son was just six years old. The book chronicles the author’s quest to learn more about his father and the circumstances of his death. It was her kind of a book: a hunt, a mystery, and also a memoir, the kind that evokes and explores lost worlds.

That night in her hotel room above a quiet side street once home to several old-time Chicago mobsters, she opened the book and began to read. For some reason, perhaps from contractions and expansions of old beams and joists, noises like cracking knuckles emanated from the walls and ceiling all night long. Michael Hainey’s words also popped from the page, filling her head as she read:

“One reason I ask so many questions, maybe why I became a reporter: It’s what happens when you have a dead father. Even now, my boyhood so far behind me, I believe I might have made something more of my life had my father lived. Had he lived to share with me his secrets of life. His knowledge. To this day still, I scavenge for scraps in the hearts and minds of men I meet. Forever searching, believing the answers are out there. Somewhere.”

The passage made LW recall her own father. That last time she saw him. It was her eleventh birthday, a week before Christmas. She had seen him only a few times since her mother remarried and they’d moved away at the beginning of the previous June. He had stalked them for a few months, revving his old Dodge truck as he’d tear around the neighborhood. Eventually he gave up, except for this last visit. Her sister was with him, the one who had stayed behind with him instead of moving on.

He passed an unwrapped birthday present to her through the front door. It was sleeveless, scratched 78, one of those plastic yellow “kiddie” records that small children played on portable record players in the ‘40s and ‘50s. She stared at the title: Rudolph the Red-Nosed Reindeer.

Her sister took her aside. She whispered how their dad was broke and sick and it was the best he could do. LW thanked him, hugged him, said good-bye. Someone closed the door and he and her sister left. Five years later he was dead.

———-

To the best of her knowledge, her father never visited Chicago, although it is possible he may have driven through or near the town on a trip he took through the Midwest as a young man in the 1930s. She remembers he once mentioned being amazed by the size of the corn stalks in Illinois that he saw in passing, stalks much taller and thicker than those that grew in their native Maryland. Whether he saw Chicago or not, there is something about the place that speaks of the man to her. And she can never quite figure out what that something is, but she keeps going back.

Some of the older-looking Chicago streets do remind her of parts of their hometown her father frequented: Hopperesque storefronts and diners, back lots and barber shops, gas stations and train tracks. In her minds-eye she sees him walking alone in these places, light jacket over paint-flecked shirt and pants, collar up, back sloped, hands in pockets, a Sherwin-Williams hat on head.

Maybe it’s the old news stories that still reverberate from some of Chicago’s Depression-era buildings, stories he, an avid reader, must have devoured. She learned from an aunt that as a young man he closely followed the exploits and escapes of John Dillinger and other colorful gangster types in the daily papers. Or maybe it’s remnants of The Depression itself, those hard years that destroyed his youth, remnants that still linger about some Chicago streets and alleys.

A few days later as she walked across town, headed toward Powell’s Books, LW found herself at the Golden Apple, a favorite diner from years past. She used to meet up with her son and other actors at the restaurant after their comedy shows at the nearby Atheneum Theater. She decided to have an early lunch, remembering how she had once lingered there over pancakes at midnight, savoring that joy of being on vacation, of not having to be any particular place at any particular time. Then she thought: Maybe that’s it. Freedom. Trips to Chicago always meant freedom to her. And her father’s trip to the Midwest had been his one gesture toward a kind of freedom. But his family in Maryland–his parents and nine siblings– still struggled to recover from the loss of their home and business in a devastating fire. Responsibilities would pull him back home. He had to turn down the opportunity for higher education offered by his friend’s family in Missouri.

She took a booth by the front windows and ordered sliders and fries. While waiting, she gazed out the windows onto St. Alphonsus Church and the overcast sky that always seemed to hang over Lincoln Avenue.

Coffee. Random thoughts. Then back to the book. She opened to the place she had left off and read:

“Chicago. I am of that place. Spires loom. The sky, a soiled shroud.”

Well, yeah. Tell it. Reading on, she became the author’s conjoined twin, comparing his father’s obituaries (each of which differed from the other), poring over the contents of his father’s wallet, and visiting his father’s haunts in the hope his story would reveal itself.

She downed cup after cup of coffee, riveted to passages such as this one in which Hainey recalled toasting his dead father with a glass of watery scotch.

“…I want to be that man. The dead man. I envy him. I want his power. The power, years later, that you have over someone. Still. Your absence is greater than your presence. Presence is fleeting. Presence is easy. But absence? That’s eternal. The great constant.

“Absence is everything.”

And absence is everywhere in Chicago, she thought, thinking of its fires and shootings and drownings, its people and places lost to time. A paradox. Absence trumps presence and thereby becomes. . . presence?

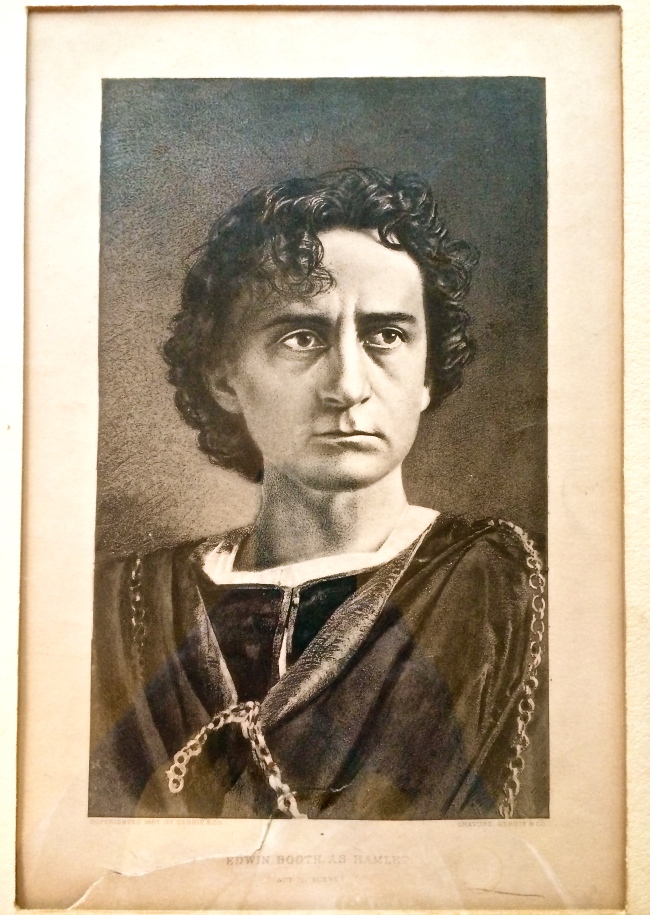

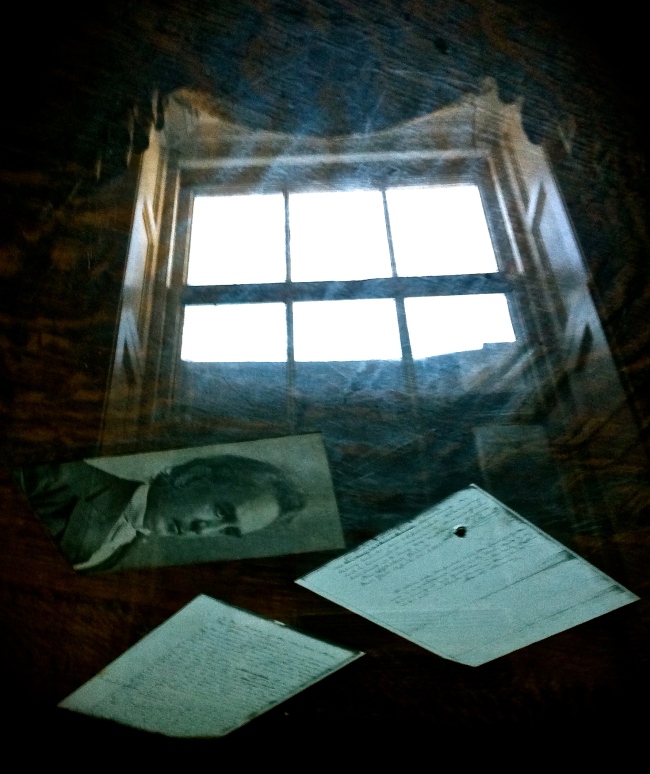

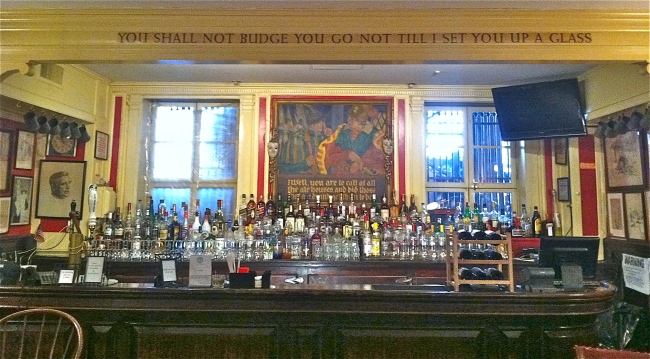

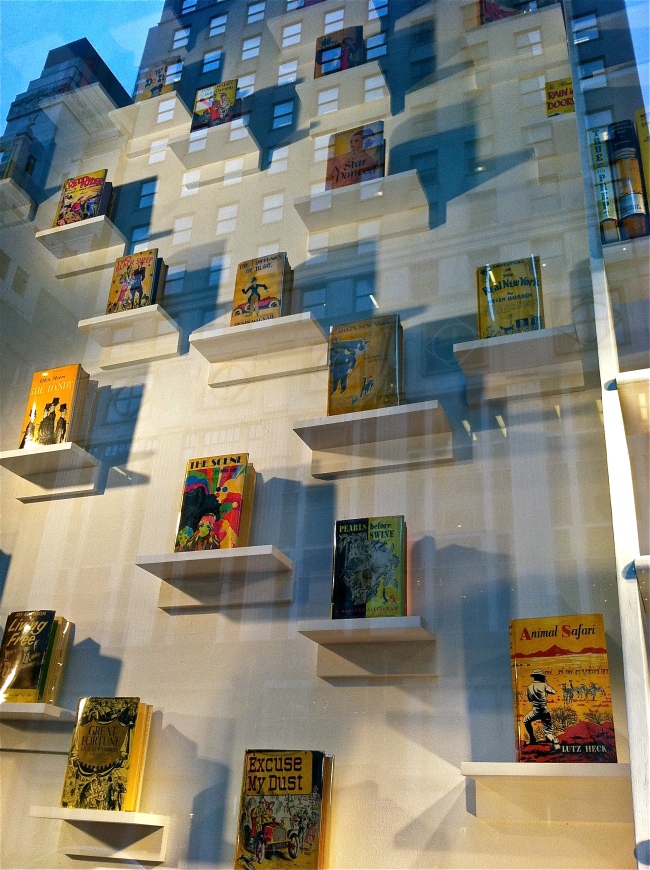

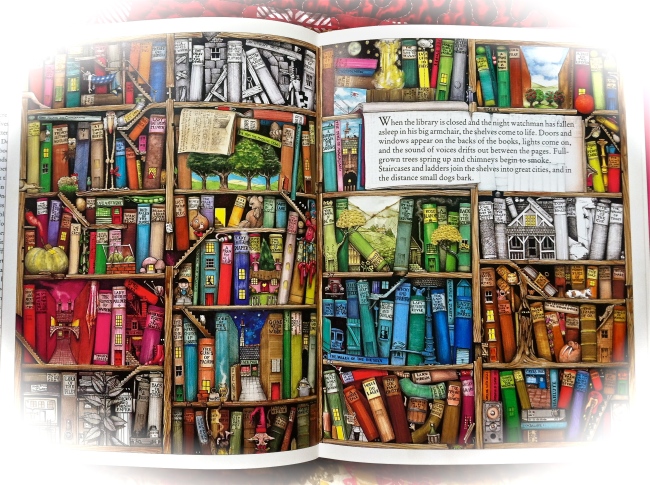

Maybe that’s where the ghosts come in. Chicago is a city of ghosts, those presences of absence. A library of books written and unwritten.

One evening it snowed, a last trace of snow following a brutal winter. LW had a cheap dinner at a soup place on Broadway before returning to After Visiting Friends. Page 179. The part where Hainey is heading north on Lake Shore Drive on his way to the hospital where his father had been pronounced dead years before.

“I love this drive. The city on my left, the lake on my right. This is the route he would’ve taken that night. I see him in his LeSabre. Window down. Cool air streams in. The air that night rich with the first whiffs of spring. Maybe the radio’s on. The dashboard, big and wide. His face, illuminated from below. No seat belt. A time before restraints.”

She could feel the cool air from The Lake as someone entered the restaurant, air that also carried the first whiffs of spring, even as it began to snow one last time. The song Norwegian Wood played from an overhead speaker, a song almost half a century old, and yet somehow quite fresh. She lowered the book as the vibrating twangs of a sitar filled the room, music played by one dead man and sung by another. Dead, yet present, NOW, present in the music like Michael Hainey’s father was present through the book I had in my hands. Absence is everything.

Or, maybe, she thought, Marvin Gaye had it down. Everything is everything.

She stuck a straw wrapper into the book to mark the page, paid her check and stepped outside to return to the hotel. And then, just as she lifted her camera to record the snowy night, a man passed by who looked a lot like the young lost newspaperman of the book—dark hair, coat, glasses.

Do ghosts ride bikes?